Caring for

the windows of

the soul

Ophthalmology is one of the most study-intensive specialties in medicine. Several recent Havergal graduates have chosen it as a profession. They are passionate about the work they do, the challenges they face, and the difference they make in their patients’ lives.

Written by Naomi Buck ’90

Photo by Kayla Rocca, Galit Rodan, and Sarah Palmer

Many of us take our vision for granted. It is so inextricably linked to our experience of the world. It’s just there. Unless it’s not.

Losing eyesight to disease, degeneration, or trauma can be devastating. Countless surveys have found that people value eyesight above all other senses. This makes the work of ophthalmologists, the medical doctors that diagnose and treat eye damage and disease, incredibly important. At times, almost magical.

“Restoring vision is pretty much the greatest thing you can do for a person,” says Dr. Cathy Eplett ’77, who has been in practice for 33 years.

Ophthalmology is as multifaceted as the eye itself. It requires an understanding of the eye’s intricate anatomy and the interplay of photoreceptors and nerves that, in connection with the brain, enable us to see. The journey to become an ophthalmologist is exceptionally long: four years of undergraduate studies, four years of medical school, five years of a residency in ophthalmology, and often a year or two of a subspecialty beyond that. But coming out the other end, the career offers breadth and flexibility, a combination of clinical work and surgery, and tremendous rewards.

Even at 65, Cathy can’t imagine retiring. While she relinquished her hospital position at Scarborough General Hospital last year, she continues to run a practice out of a clinic in Don Mills, and to perform surgeries at the Herzig Eye Institute, a private clinic in Toronto. She and her husband, a litigation lawyer, are the devoted owners of two Birman cats, Wolfie and Skye.

Long before starting in grade 10 at Havergal, Cathy knew she wanted to be a doctor. She recalls the worms she collected and dissected during childhood summers spent at a family cottage in Muskoka. After enrolling as a medical student at McMaster University, a neighbouring cottager invited Cathy over for a visit. By summer, Lois Smallman was a champion golfer and consummate country clubber, but for the rest of the year, under her maiden name (Dr. Lois Lloyd), she was a neuro-ophthalmologist and trailblazer in the otherwise very masculine domain of surgeons. Over tea, Lois suggested that Cathy explore ophthalmology and arranged for her to do an elective at Sick Kids Hospital. Cathy found it fascinating.

She experienced a minor setback when she was invited to observe retinal detachment surgery on a 13-year-old boy. As the surgeon peeled back the conjunctiva (the thin, clear membrane covering the eye) and unhooked the muscles that hold the eye in place, Cathy passed out cold. She resurfaced briefly to see the surgeon making his first cuts, only to pass out again. When she woke up, she found herself on a child’s gurney, parked in the hall.

“I was teased about that for years,” she says. Nonetheless, Cathy was confident in her choice and was accepted into the residency program at the University of Toronto. “It seemed that ophthalmologists just loved what they were doing. They were having the most fun.”

To the outsider, fun may not be the first word that comes to mind to describe the complexity, rigour, and high stakes of this profession. But Cathy describes the satisfaction of treating eyes, often called the windows of the soul, as immeasurable. She believes this is what makes ophthalmologists, on the whole, such a contented bunch.

“Restoring vision is pretty much the greatest thing you can do for a person.”—Dr. Cathy Eplett ’77

Photography by Kayla Rocca

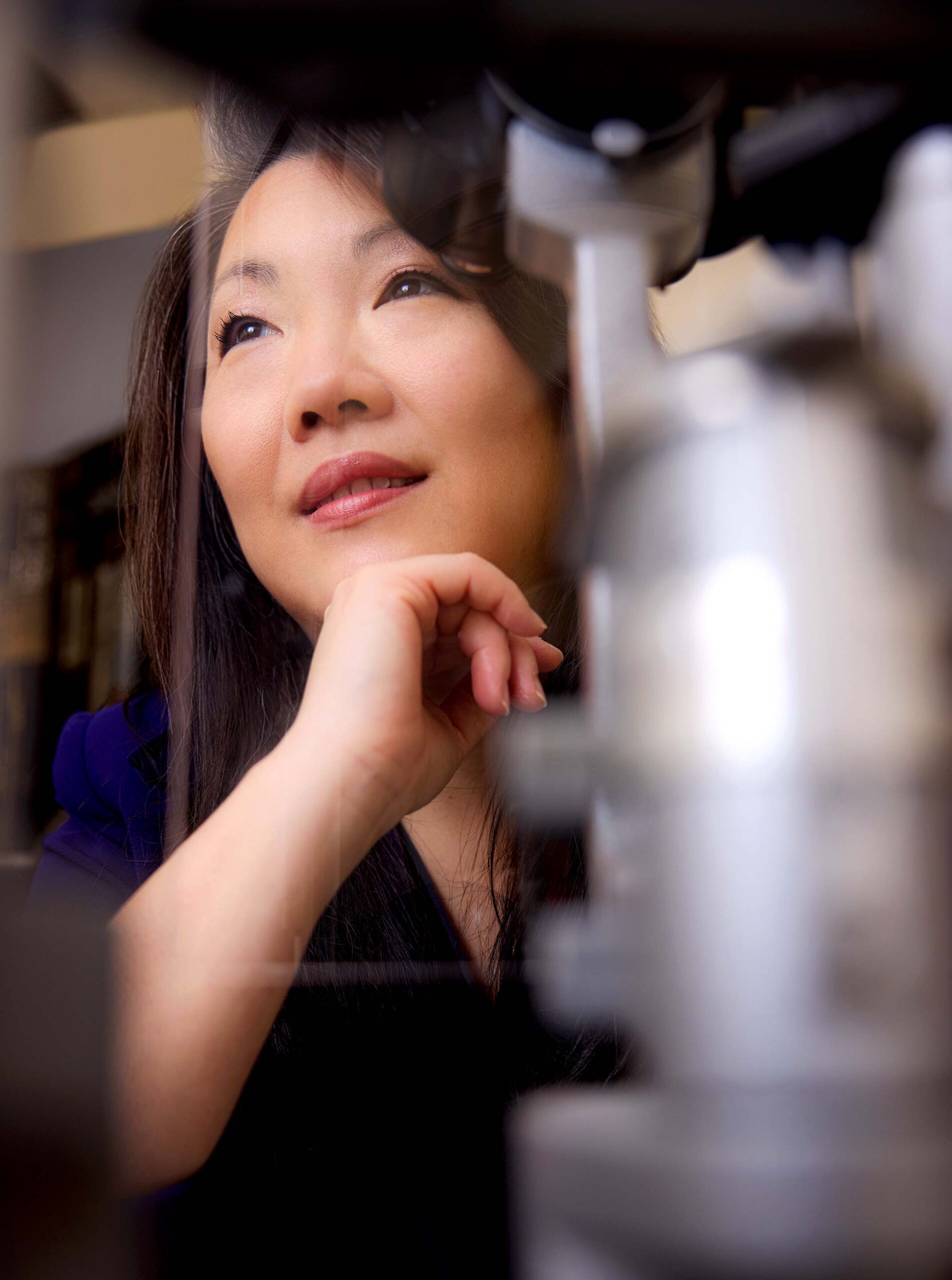

Unlike Cathy, Dr. Clara Chan ’97 was anything but dead set on a career in medicine. After graduating from Havergal, she was an economics major at Stanford University. Like many of her peers, she was drawn into the tech boom of the late 1990s. She worked at Goldman Sachs on Wall Street for one summer and at Google for another. But when the tech bubble burst in 2001 and many of her friends found themselves jobless, she was glad to have kept her options open. She enrolled in medical school at Queen’s University.

Clara calls herself a fixer and problem-solver. She found internal medicine “quite cerebral” and preferred the immediacy and visuality of the eye, describing diagnosis as largely a matter of pattern-recognition. While she enjoyed surgery, she quickly realized that she “didn’t love the bloody stuff.” Eye surgery, she says, is quite clean. She loves it. Perched on a stool, her feet manage the power, flow, and suction pedals as she watches the tips of the high-precision tools in her hands through a microscope and listens for the beeps and dings of each machine. It’s completely absorbing.

Clara specializes in the cornea, the clear, domed window on the eye. Dealing with “some of the sickest eyes,” she is one of a handful of ophthalmologists in Canada who conducts limbal stem cell transplants. These procedures help to reduce the scarring on the cornea that can result from chemotherapy, chemical burns, firecracker injuries, or congenital conditions. She also regularly performs corneal transplants and, in addition to teaching in the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Toronto and training international ophthalmologists in the cornea fellowship program at the Toronto Western Hospital, is Medical Director of the Ontario division of the Eye Bank of Canada, overseeing the donated supply of ocular tissue and corneas that are commonly used in replacements and repairs. In 2023, The Ophthalmologist put Clara on its Power List, recognizing the top 100 most influential figures in ophthalmology around the world.

Balancing all this with family life—Clara is married to a physician, and they have a 9-year-old son—has meant letting go of certain expectations. “At work, I have a lot of control. At home, not so much,” she says, adding that she has learned to accept the fact that she will never make the mum’s coffee group at 9 am, or show and tell at 2 pm. Seeing an average of 60 to 80 patients a day in her clinic, she is wary of the potential for burn-out in a profession that is seeing ever higher patient volumes.

unit at the Scarborough Health Network Centenary Hospital. Photography by Galit Rodan.

Photography by Galit Rodan.

This is something that Dr. Andrea Leung ’00 struggles with. As one of the few pediatric ophthalmologists operating in the Greater Toronto Area, Andrea has trouble turning young patients away, knowing that they don’t have much in the way of alternatives. In addition to her pediatric patients, Andrea also practices general ophthalmology out of her clinic in Scarborough. Appointments there are being booked six to nine months out.

The problem of wait times is systemic and results from improvements in medical technology, combined with an aging—and growing—population. People are living longer, and treatment options have improved, meaning better outcomes for patients but also more work for ophthalmologists. Andrea cites macular degeneration as an example of a disease that used to mean blindness. Now, the condition, which causes a gradual loss of central vision, can be managed with monthly eye injections.

“It’s hard to keep up,” she says. “It’s also hard to scale back.” After eleven years in practice, Andrea finds she becomes invested in the lives of her patients, especially the ones she meets as newborns or young children. “They start to feel like your own kids,” she says, adding that many of her patients greet her with a hug.

Andrea spends one day a week in the neonatal intensive care unit at two Scarborough hospitals. Some premature babies develop retinal disease that can lead to retinal detachments and blindness. These babies are now routinely screened and treated. Among the pediatric eye conditions that Andrea treats are strabismus (misaligned eyes), amblyopia (“lazy” eye), blocked tear ducts, ptosis (droopy eyelid), nystagmus (shaking eyes), and the various eye manifestations of genetic diseases and developmental disorders.

“People assume this work must be sad,” says Andrea, “but it’s not. Kids are so resilient. Their parents may be worrying about their conditions and their futures, but kids just adapt to what they have. It’s inspiring.”

“Kids are so resilient. Their parents may be worrying about their conditions and their futures, but kids just adapt to what they have. It’s inspiring.”—Dr. Andrea Leung ’00

eyelid surgery, cosmetic eyelid surgery, lacrimal surgery,

and periocular reconstructive surgery. Photography by Sarah Palmer.

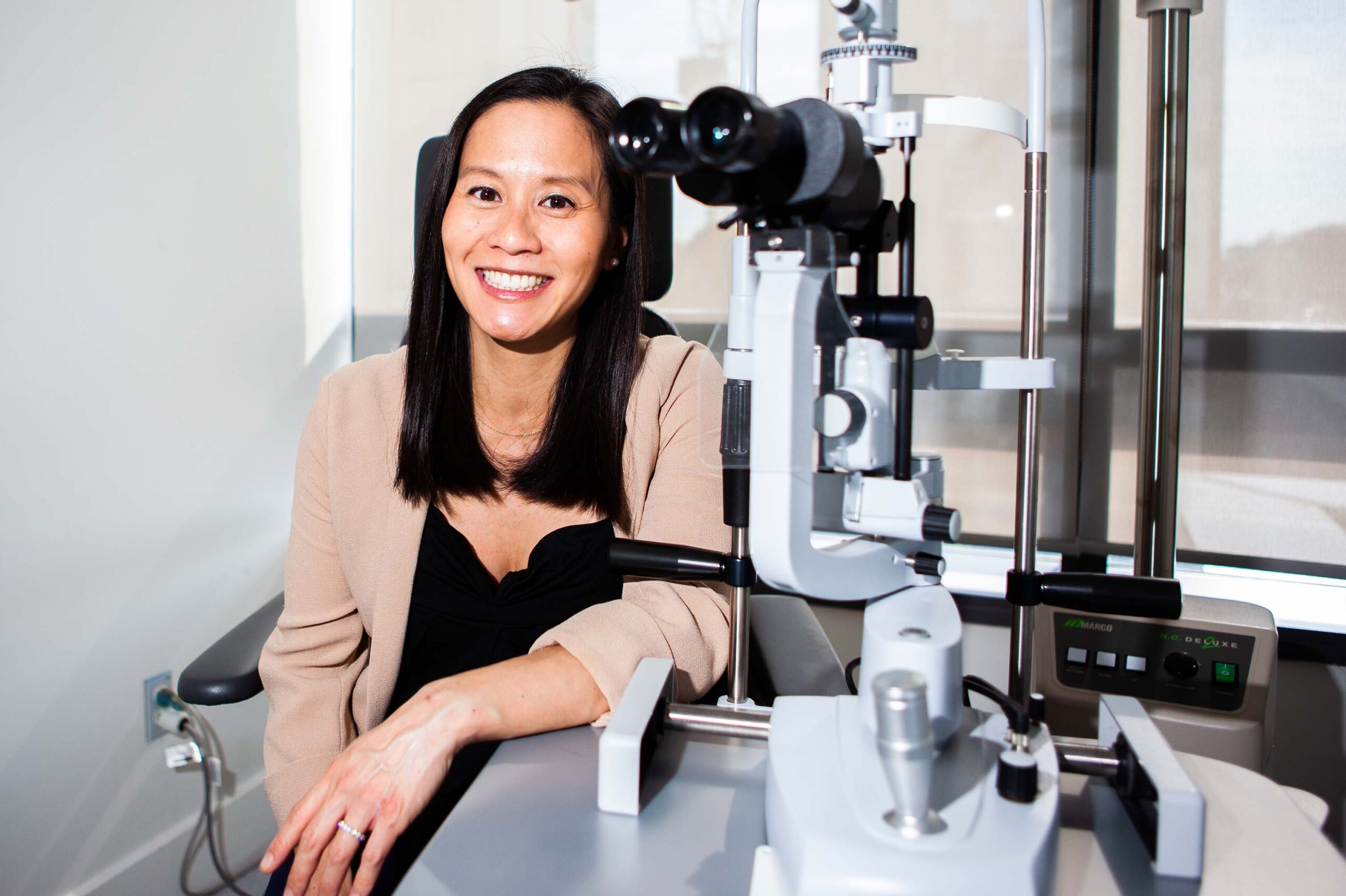

As the mother of a four-year old daughter and two-year-old son, Andrea often compares notes with Dr. Victoria Leung ’06 (no relation), who is also straddling young motherhood and a career in ophthalmology. Victoria has been practicing for three years, while also parenting a toddler son and soon-to-arrive baby girl.

Breadth is what drew Victoria to ophthalmology, and the opportunity to combine medical practice with surgery. Having completed her undergrad at Brown University in a unique program that combines medical studies with the liberal arts, she did her medical and ophthalmology training at the University of Toronto, followed by a fellowship in oculoplastic surgery at the Université de Montréal.

As an oculoplastic surgeon, Victoria performs surgeries of the eyelids, tear ducts, orbit (eye socket), and face. Her cancer cases require collaboration with diverse specialists: plastic surgeons, dermatologists, radiologists, and oncologists. It’s a team effort that takes her back to Havergal, where she learned how to leverage the strengths of the community as a whole. “We set ourselves lofty goals,” she says, “but we achieved them through collaboration, not competition.”

Victoria’s favourite surgeries are blepharoplasties (eyelid repairs) and dacryocystorhinostomies (unblocking tear ducts). Ptosis, a droopy eyelid condition that can be caused by age, disease, or neurological degeneration, requires a very delicate fix: removing tiny portions of fat and skin, while tightening tendons. Victoria enjoys the intersection of form and function that such surgeries entail.

“It’s beautiful,” she says. “The level of precision and innovation. You’re dealing in microns and millimeters. And the outcomes are better than ever.” She also performs some cosmetic surgeries—lifts and rejuvenations around the eye—but says her approach is conservative; she is careful to ensure that the patient’s expectations are realistic.

“It’s beautiful. The level of precision and innovation. You’re dealing in microns and millimeters. And the outcomes are better than ever.”—Dr. Victoria Leung ’06

In these conversations, and in all her work with patients, Victoria is constantly reminded of the importance of communication: ensuring that doctor and patient truly understand each other. It’s one of the things that Dr. Jennifer Calafati ’01 enjoys most about the profession.

Jennifer is a people person. She describes herself as (take out “In her time at Havergal,”) a very social student who loved extra-curriculars, particularly theatre. Today, Jennifer is grateful that Havergal set such high academic standards and encouraged her to pursue a professional career. It landed her in medical school at McMaster University, where she thrived. She completed her ophthalmology residency at the University of Toronto with two awards, one for the resident with the highest academic standing over five years.

Initially, her feeling about ophthalmology was “anything but.” But gradually she realized that she enjoyed the highly visual nature of ophthalmology and its direct impact. Unlike some other specialties that routinely require extensive imaging and lab work, diagnosis in ophthalmology often requires no more than a physical examination.

“You can make a drastic difference quickly,” she says, citing cataract surgery as an example. The technology involved in removing the clouded lens and replacing it with a new one has improved so vastly that patients can often hardly believe the results. “They’re over the moon,” she says. “You get a lot of gratitude.”

Most of Jennifer’s work is on cataracts and glaucoma, a disease of the optic nerve that causes gradual vision loss and can lead to blindness. Both mainly affect older people. “There’s lots of business going around,” she says. The volume of work means that she needs to connect quickly with her patients, who come from all cultures and walks of life; again, communication is key.

In addition to her clinical and surgical work, Jennifer is a lecturer and the Director of Undergraduate Education in the Ophthalmology Department at the University of Toronto. She has two young children and a partner who is staying home for now. Unlike many other medical specialisations that have moved to a more hybrid practice since the pandemic, ophthalmology remains very much in person. But that’s also what Jennifer likes about it.

Because, as technical and clinical as the work can be, what ultimately sticks in these doctors’ minds are their patients. Cathy Eplett ’77 remembers being on the night shift at Scarborough General Hospital when an 18-year-old boy walked in with his parents. He had been at a party that was crashed by uninvited guests. A fight broke out and he was smashed in the face with a beer bottle. His eyelid had been torn off and his eyeball sliced in two.

“I’ll do what I can,” Cathy remembers saying to the parents, glad for her extra training in oculoplastics. The surgery lasted most of the night. Cathy was able to save the boy’s eye and reconstruct his eyelid. He didn’t regain perfect vision, but he was legally able to drive and could still play basketball. The family’s gratitude was overwhelming.

“We all have stories like this,” says Cathy. “It’s what keeps us going.”

More Profiles

- Old Girl/ Alum, Profiles

- Old Girl/ Alum, Profiles

- Old Girl/ Alum, Profiles